Americans spent an average of $1,432 per person on prescription drugs in 2021, more than citizens of any other country in the world. As a result, 31% of adults reported that they were unable to take their prescription medicines as prescribed at least once over the past year in 2023.

Surprisingly, drugmakers are not the largest beneficiaries of this largesse. Rather, it is the obscure middlemen, prescription benefit managers (PBMs), that benefit most from America’s broken prescription drug supply chain.

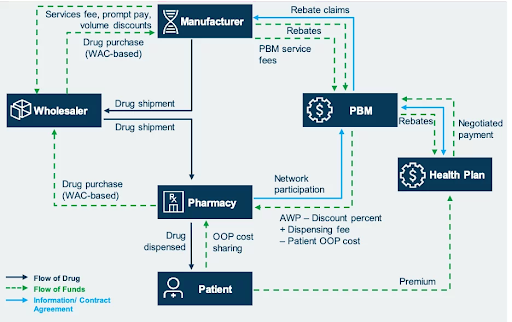

PBMs act as intermediaries between pharmaceutical companies and health insurers. PBMs manage formularies, lists of drugs covered by various health plans, for insurers. Formularies have multiple tiers of drugs for which patients pay different copays or coinsurance rates, which determine the amount paid out-of-pocket.

Drugmakers negotiate with PBMs to have their medicines included in a formulary and on a preferable tier. Formulary position is key to a drug’s success because it determines whether patients will have access to the drug and at what cost. Thus, PBMs have lots of power in these negotiations.

In order to include a drug on their formulary, PBMs demand rebates or discounts from the drug’s list price. In theory, pharmacy benefit managers pass on these rebates to plan beneficiaries, but, in reality, they keep most of the rebates for themselves.

These rebates create a perverse incentive for pharmaceutical companies to raise the list price of medicines so that they can afford to offer higher rebates than their competitors to PBMs and thus reach more patients. In other words, rebates cause the market to favor higher rather than lower priced drugs. A 2021 Senate report revealed how these practices led to insulin prices of more than $300 per vial, despite the fact that each vial costs only $2 to $4 to produce.

High list prices affect uninsured people the hardest. And although health insurance covers most of the cost of prescription drugs, copayments or coinsurance costs are often based on the list price of the drug rather than the lower price negotiated by PBMs. As a result, even insured patients can end up with huge bills for prescription drugs.

Spread pricing is another problematic tactic used by PBMs to increase their profits. With spread pricing, PBMs reimburse pharmacies at a rate lower than what PBMs are paid by insurers, keeping the difference as profit. Sometimes, PBMs will even reimburse pharmacies at a lower rate than what pharmacies pay for a drug, causing pharmacies to lose money.

Spread pricing adds up; it cost Ohio’s Medicaid program $223.7 million in 2017. This is just the money spent by Medicaid in one state over one year, so it represents only a small fraction of the money that PBMs make from spread pricing.

It is hard to know exactly how much PBMs profit from these practices because they are notoriously opaque in their business practices. However, several PBMs are Fortune 25 companies, while pharmaceutical companies are relegated to the Fortune 500.

PBMs are able to get away with this anticompetitive behavior because they are both horizontally and vertically integrated. The top three PBMs make up about 80% of the market. The largest PBMs are also vertically integrated with insurance companies, pharmacies, and provider services.

This consolidation makes it harder for drugmakers to reach patients without paying large rebates. It also helps to obscure the flow of money through the industry, and it provides PBMs an incentive to steer patients towards their own pharmacies, to the detriment of patients and independent pharmacies.

Luckily, some progress has been made in combating the influence of PBMs over drug prices. Congress is currently considering the Lower Costs, More Transparency Act which includes several reforms to PBMs. Additionally, several states have made reforms that save them millions of dollars annually.

As Hawaii suffers the highest cost of living in the United States and a budget shortfall of hundreds of millions of dollars, any policy that could save patients and taxpayers money should be seriously considered.