The goal is clear. The United States and 193 other countries have joined the Paris Climate Agreement, which seeks to limit “the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels,” but preferably below 1.5°C. Recent research shows that warming must be kept below 1.5°C in order to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

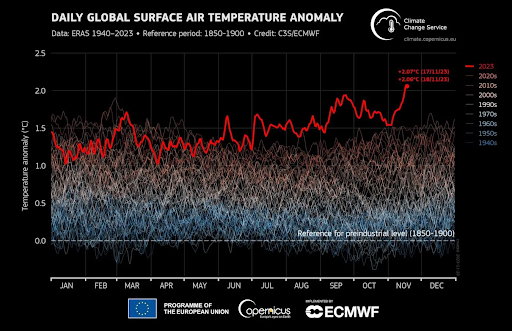

However, whether the world will reach this ambitious goal looks uncertain. On Nov. 17 and 18, the global average temperature surpassed 2°C above pre-industrial levels for the first time. And, a recent U.N. report found that if countries fully implemented their current emissions pledges (and that’s a big if), it would only limit global temperatures to 2.5°C to 2.9°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

Clearly, more must be done if the world is to meet its climate goals. Although some progress has already been made with the Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S. can and should reform permitting and implement a carbon tax in order to cut emissions.

To date, the Inflation Reduction Act, is the largest climate change related legislation in American history. The law includes hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies for green technology, mostly in the form of uncapped tax credits.

Although the law is expected to reduce America’s carbon emissions to 40% below their 2005 levels by 2030, it falls short of President Biden’s goal to reduce emissions to half of their 2005 levels by 2030. Not to mention, some protectionist provisions of the law have irked the European Union and other American allies. While the law may be imperfect, it is an important start towards reducing carbon emissions.

31% of carbon emissions in the U.S. come from electricity generation, and demand for electricity will increase as more sectors are electrified. Therefore, the expansion of renewable energy and the associated infrastructure, like batteries and long-distance transmission lines will be necessary for the U.S. to meet its climate goals.

The Inflation Reduction Act included hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies for renewable energy. However, the projects funded by the law have begun to face regulatory roadblocks: it takes years to get permits for solar and wind farms. And, building transmission lines takes even longer.

Ironically, the largest barriers to renewable energy are often laws that were designed to protect the environment, such as the National Environmental Policy Act. When NEPA was passed in 1969, “high-density urbanization” and “new and expanding technological advances” were described as threats to the environment. Today, however, we know that dense cities and renewable energy technology are crucial to protecting the environment, but, while our understanding has changed, our laws haven’t.

In fact, since NEPA was passed, many states, including Hawaii, and thousands of local governments have created their own environmental regulations that are stricter than NEPA. These regulations create a litany of problems for anyone trying to build anything—unless they happen to be building cell towers or natural gas pipelines. That’s because Congress has recognized the need to streamline the permitting for what was considered to be necessary pieces of infrastructure.

Congress passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996 in order to prevent local residents from using environmental laws in order to block cell phone towers. The law prevents local governments from outright banning cell towers and local residents from filing environmental lawsuits based on bogus claims, but it still allows cities and states some control over the aesthetics of the towers. As a result, we now have a nationwide cell phone network.

Similarly, Congress gave one agency, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the power to approve interstate natural gas pipelines that otherwise would have to be approved by hundreds or even thousands of local governments and landowners. FERC must still consult these local governments and landowners, but it gets to make the final decision. FERC simplifies what otherwise would’ve been an extremely cumbersome process.

Building wind turbines or transmission lines should be as easy as building cell towers or natural gas pipelines. Congress should create expedited processes for permitting renewable energy projects that are based on these successful processes.

Additionally, although the Inflation Reduction Act incentivizes renewable energy, it does little to disincentivize fossil fuel use. In fact, the law opens up more federal land and offshore waters to oil and gas drilling. In order to disincentive fossil fuel use, America needs a carbon tax.

Currently, the negative externalities, or negative effects of fossil fuels are borne not by the producers or consumers of fossil fuels but by everyone, regardless of how much fossil fuels they use. People and companies will be slow to change their behavior because there is no incentive to do so. If they change their behavior, they will face higher costs than others who choose to maintain the status quo.

Carbon taxes are a Pigovian tax, a tax designed to change behavior. Carbon taxes are designed to make carbon emitters feel the effects of their emissions directly rather than indirectly by putting a price on carbon.

In this way, carbon taxes give people and companies a financial incentive to emit less carbon. Where carbon taxes have been implemented, such as in British Columbia, carbon emissions have decreased. Additionally, there is evidence to suggest that British Columbia’s carbon tax actually increased GDP.

This increase in GDP is probably due to the fact that carbon taxes are much more efficient than other types of incentives for renewable energy. For example, consider the Inflation Reduction Act: according to the University of Massachusetts Amherst, each green job created by the law will require over $100,000 in public and private investment. Conversely, a carbon tax generates revenue, and allows the market to determine the best way to go about decarbonization.

Climate change is a daunting problem, but people have been thinking about solutions to the problem for decades. Many of these solutions, like permitting reform and a carbon tax are simple and already proven. If the United States is serious about fighting climate change, it should start implementing them.