It may come as a surprise to many that Radford High School was partially built on top of a former U.S. Navy landfill. As reported by Hawaii News Now in February, the landfill has created a myriad of problems around the school, including settling on the tennis courts and a sinkhole by the bus turnaround.

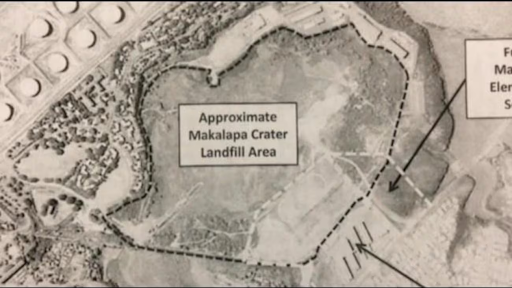

Radford’s lower campus is located inside the rim of Makalapa Crater. At one time, the crater housed a 60 meter (200 feet) deep freshwater lake. However, the lake was lost in the 1930s when the Navy began using the crater to store dredge spoils from the dredging of Pearl Harbor.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the crater was used as a salvage yard for scrap materials including “metal scrap, engine parts, empty ammunition casings, and airplane and ship parts.” According to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, “Over 1,000 trucks a day of waste material were delivered to the site.”

At the crater, what was salvageable was salvaged and what was burnable was burned in an open burn area. However, unburnable waste, including “glass, metal, porcelain, concrete, asphalt, ACM [asbestos containing material], and munitions-related debris,” was disposed of into the crater. After World War II, the landfill was buried, and Radford was built in 1957.

School officials first encountered problems around twenty years ago, when the irrigation systems for the baseball and softball fields were installed.

“We found all this material, so we had a guy come with a backhoe,” said Athletic Director Kelly Sur, “We found the back-end of a Humvee! So, we think, ‘what’s going on?’ So, we dig it out and tell the state. We didn’t hear anything [from the state].”

Further problems were encountered when the John E. Velasco Stadium was built in 2013.

“When they started construction on the track, the same thing happened, things were coming up. But then, they saw that, in some areas, the ground was really discolored, so they had a suspicion that this could be more,” said Principal James Sunday, “And then they found some ordinance, items like old fuses for bombs, so the concern came up that there could be unexploded ordnance in the dump site.”

That prompted the state to pause construction and get the Navy involved.

The Navy removed over 10,000 cubic meters (14,000 cubic yards) of contaminated soil. During the excavation, “burned soil/debris, boilers, industrial metal pieces, wire rope, ACM [asbestos containing material], and large pieces of concrete” were discovered. Luckily, no unexploded ordnance was discovered, but over 800 “expended, empty, or inert” pieces of ordnance were discovered.

After the Navy finished excavating the topsoil, they covered the still-contaminated subsoil with a geotextile fabric and placed a layer of clean fill dirt over it.

“When they started digging up our track, it was supposed to be a one year job,” said Sur, “It took almost three or four years.”

After the stadium was finally built, the Army Corps of Engineers took over responsibility for the remainder of the remediation. Subsequent testing discovered contamination and buried debris across Radford’s lower campus.

Chemicals of Potential Concern (COPCs) at levels that “pose an unacceptable risk to human health” were discovered near the gym, practice field, and bus turnaround. A feasibility study that identified specific actions to be undertaken to mitigate the contamination was completed in 2021.

However, the Corps has been slow to act.

“They did testing all over the place, but since that time, nothing’s transpired. Nothing. Zero,” said Sur, “If you look at the tree line where the construction is, where PE is, they got that tarp with the fence. The state did that because the military wasn’t doing anything. That’s all contamination under there.”

Sur drew parallels between the federal government’s response to the issues at Radford and their response to the Red Hill water crisis.

“The thing that bothers me the most is that this is basically a military school. You look at the drinking water problem that we had and now with Radford with the contamination. You’d think that the federal government would do a little more in regards to addressing the problem,” said Sur.

The Navy’s record of environmental stewardship in Hawaii is far from exemplary. A 1983 Navy report identified 30 sites with possible contamination. Pearl Harbor was added to the EPA’s Superfund list in 1992—and it has yet to be removed.

For Sunday, the most challenging part of dealing with the Corps has been their lack of a clear timeline.

“There’s no definite timeline,” said Sunday, “We don’t want it obviously to be a 10 year timeline. We want it to be sooner than later.”

Sur was skeptical that the Corps would do anything to address the problem without significant pressure.

“It seems as though it takes publicity for anybody to move a finger,” said Sur, “So hopefully this follows through and they come up with a solution. I think right now, the DOE and Corps of Engineers need to come to an agreement. And they need to understand that they gotta work together.”

Despite the issues posed by the landfill, school officials wanted to emphasize that students and staff were under no immediate threat.

“Safety is our number one priority,” said Sunday, “We are confident with the guidance of the Department of Health, Department of Education, and Army Corps of Engineers, our playing surface is safe at this time.”